NZ's Green Bank risks being regarded as expensive objet d'art

Accurate performance measurement is a prerequisite in gauging the effectiveness of expenditure

This is an OpEd piece first published in the National Business Review 1 July 2023

One of the Government’s tools to tackle climate change is the use of a Green Bank, the New Zealand Green Investment Finance (NZGIF) which, in its own words, aims “to facilitate and accelerate investment that can help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions”.

It plans to do this by: (1) investing to “reduce emissions”, on (2) a “commercial basis”, through (3) “attracting “co-investors”, whilst (4) demonstrating “the benefits of low carbon investment”.

The NZGIF, as NZ’s Mindful Money notes, is an ‘impact fund’ – where investments, according to the Global Impact Investment Network, are “made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return".

Measuring ‘Impact’ – perception vs reality

The ability to accurately measure and report an investment’s impact not only improves capital allocation decisions and environmental outcomes, but can counter claims of ‘impact washing’.

Calculating the Greenhouse House Gas (GHG) attributable to an economic activity can be complex, but once established, the methodology used for attributing CO2 amounts to financed investments is intuitive and simple, and has been formalised by a global industry body, The Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF).

PCAF represents 380 institutions, including BNZ and Kiwibank, that are responsible for US$89 trillion of assets. Where there are multiple sources of funds, PCAF’s methodology allocates carbon emissions associated with a particular investment or project on a pro-rata basis (known as an attribution factor). It’s a process the former UK Green Bank, the Green Investment Group (now part of Macquarie), use in their emissions reporting. An advantage of adopting such a methodology is enhanced transparency in the measurement and reporting of carbon footprints, including emissions benefits and abatements.

In contrast to the PCAF’s pro-rata method, the NZGIF in their Emissions Benefit Report (EBR) use “100% of the project’s (lifetime) emission reduction, regardless of co- investment levels”, to generate a reduction of 580,000 to 710,000 tonnes of CO2e as at the end of June of 2022.

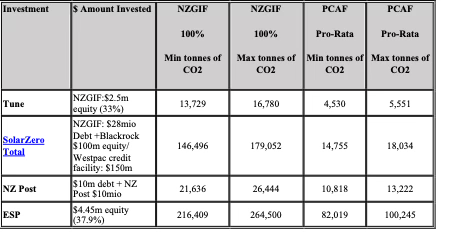

To illustrate the differences between the two approaches, the table below lists selected NZGIF’s investments from the EBR report along with, where available, co-investment amounts. Each investment has an emissions benefit number using the NZGIF’s 100% attribution approach, and a number derived from the PCAF’s pro-rata methodology.

Information shortfalls don’t permit the calculation of a pro rata emissions benefit on all the NZGIF’s investments, although by taking the available information as broadly representative of their whole portfolio, and setting this pro-rata amount at 40%, the lifetime emissions benefit number drops from 580,000-710,000TCO2 to 232,000-284,000TCO2.

Without knowing the operational lifetime of each investment it’s not possible to produce a more useful and comparative annual emissions number or, better yet, one that reflects the time value of carbon – removing one tonne of carbon today is more environmentally beneficial than removing one tonne tomorrow. Nonetheless, again referencing EBR case studies, where eight years is noted as the operational life, if this ‘lifetime’ number is applied to the whole portfolio, and using the PCAF pro-rata investment approach, the NZGIF’s annual emissions benefit equals 29,000 to 35,500TCO2.

The NZGIF claim their methodology is used by other Green Banks in reporting emission reduction impacts, but while lifetime emissions benefits can be a useful metric at the investment decision level, like choosing a project with the best NPV, they lack efficacy, on a system-wide basis, in the determination of how much carbon has been reduced.

Sources: New Zealand Companies Office/NZGIF/NBR.

Contextualising impact

Stats NZ indicates that there that there are 1.86 million households in New Zealand, comprising of 2.7 people who emit 1.6 TCO2 per capita per annum. This means (assuming an eight year ‘Lifecyle’) that NZGIF’s investments to the end of June 2022 have generated an annual emissions reduction number which is equivalent to the yearly CO2 emissions of; 16,782 to 20,543 households using their ‘100%’ approach; or 6,712 to 8,217 households using an illustrative 40% PCAF pro-rata one.

In one year alone the coal used to generate 2,159 GWh electricity emitted 1.8 million tonnes of carbon, which is the equivalent annual CO2 emissions of 416,000 households. Reducing or, better yet, totally removing the need for coal in electricity generation moves the carbon dial significantly, while the NZGIF investments, contrary to Minister James Shaw’s May 2023 statement hardly moves the needle.

How does the NZGIF stack up?

A Dollar deployed by the NZGIF looks an expensive way to reduce one tonne of carbon from the environment…

When assessing the NZGIF’s ‘commercial’ performance, aside from an absolute or relative monetary return, a useful emission impact metric is the ‘economic emission intensity benefit’ generated – the dollar cost of removing one tonne of carbon. Using $430m ($400m of funding, plus $30m of appropriations) results in the cost of reducing one tonne of CO2 via the NZGIF of $741 to $605 using a 100% attribution factor, or $1,853 to $1,514 using a 40%. pro-rata one.

By comparison, a New Zealand Carbon unit (1TCO2) in the Emissions Trading Scheme is approximately $54. Modelling by the New Zealand Treasury of a theoretical societal cost of carbon has a price of less than $250 per tonne of CO2. The UK has utilised a similar approach in calculating a shadow price for a tonne of carbon at GBP241 to GBP378, while the US sets its Social Cost of Carbon at US$190 per tonne of CO2 – both of these theoretical prices are used in their respective country’s investment and policy cost benefit frameworks.

Results don't match the rhetoric

When announcing an increase in the NZGIF’s funding levels Minister Shaw referred to a “win win” virtuous cycle of reduced emissions and recycled investment returns. Looking across the portfolio of ‘Green’ investments, the results would appear to fall short of the vision.

Unfortunately, contrary to the aim of being a ‘facilitator and accelerator of private capital’, the NZGIF’s apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree of Government.

In terms of ‘demonstrating the benefits of low carbon investment’, the bulk of their activity has been debt related, with a high concentration in asset finance markets (EVs and solar panels) that possess numerous private sectors participants – not conditions associated with market failure or an inability to access capital, including that provided, indirectly, by other Government entities. There exist other policy levers that have been successfully applied in other countries (i.e. feed-in tariffs for solar) that offer an alternative approach to a Dollar deployed by the NZGIF.

Some investments made with other public sector entities have been unnecessary, as evidenced in one case where all but one of the 60 EV vans ordered were taken on by the government owned co-investor. While in another investment, establishing a holding company (CARBN),with all the associated set up and running costs, containing a subsidiary whose business model, is in part, the provision of asset leasing and financing services, again, into Government, is duplicative and raises competitive neutrality issues.

Given the high concentration of debt financing (compounded by the low utilisation rates on committed facilities) capital recycling won’t be materially significant. Where NZGIF’s participation is cited as an example of driving private capital recycling it’s moot whether this capital has been redirected into projects that have green/decarbonisation goals.

While other countries, notably Japan, operate both a Green Bank and a Venture Capital Fund, given New Zealand’s small capital market landscape with its plethora of government investment entities, including the New Zealand Growth Capital Partners, it’s not obvious what financing need a Green Bank meets in meaningfully lowering New Zealand’s CO2 emissions.

Four years on too early to tell if NZGIF is a success?

In the 1970s Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, on asked what he thought about the impact of the French revolution, replied, ‘it is too early to tell’, the same might not be true of the NZGIF. Whilst initially constrained by a small pool of capital ($100m, later increased to $400m in 2021 and now to $700m) with a need to build up operational capability, to date carbon reduction has been small and expensive to achieve, with little to indicate this will change going forward.

To get a sense of the magnitude of decarbonisation challenge, and how a Green Bank ‘solution’ comes up short on addressing it, if forecasts of 150,000 annual electric vehicle sales prove correct this will require an additional 367GWh of electricity generation every year just to satisfy charging needs. Currently, seventeen on-shore wind farms, with a 690 MW capacity, generate 2,282 GWh of electricity, an amount greater than that derived from burning coal (with its associated 1.8million tonnes of annual CO2 emissions); so it’s easy to see how projects such as the New Zealand Super Fund’s engagement with Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners to assess the potential for a 1GW capacity offshore wind farm can be a more impactful decarbonisation solution than that currently delivered by the NZGIF.

Accurate performance measurement is a prerequisite in gauging the effectiveness of expenditure. Without such a yardstick of ‘success’, especially in a period where there are many societal and environmental needs to be addressed by a finite pool of Government resources, New Zealand’s Green Bank risks being regarded as an expensive piece of policy Objet d’Art – visually decorative, but not particularly practical or impactful.